If you are thinking about selling yourcompany, planning succession, or seeking financing, understanding what your business is truly worth is essential. Valuation is both an art and a science. It analyzes financial results and operating reality, then tests how the market is likely to price risk. In the end, the price a buyer will pay depends on more

than numbers; it depends on the durability of your cash flows and the credibility of your story. The goal of this work is to establish a defensible estimate of value and define the most likely sale price range for your business.

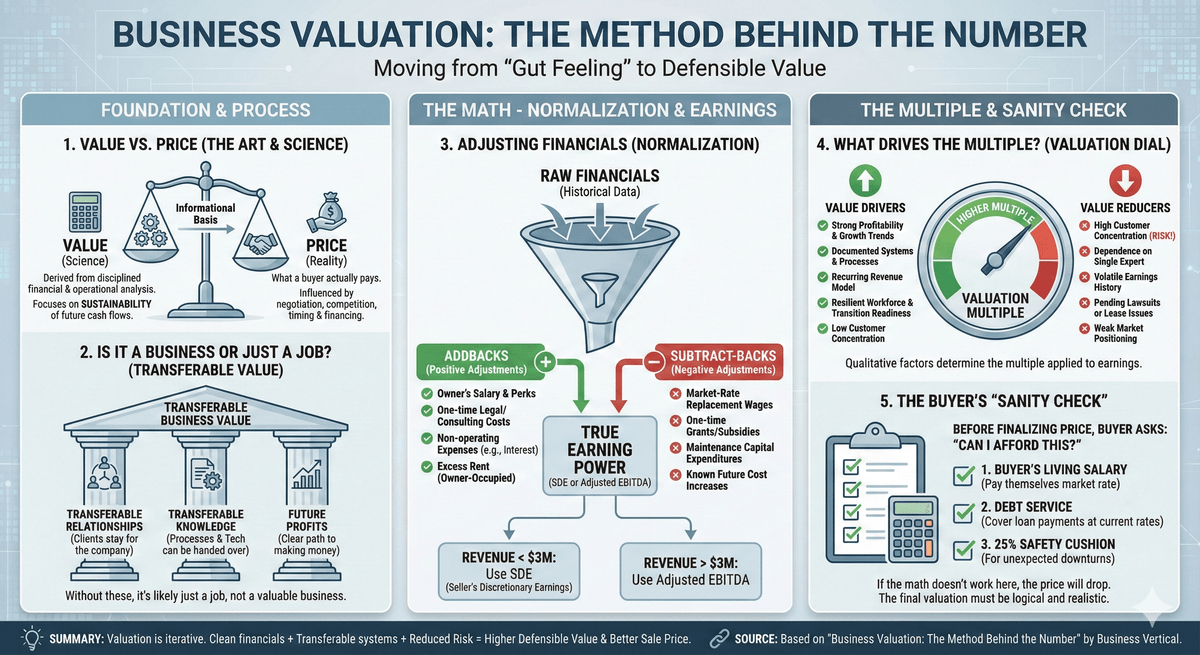

Part I: Understanding What “Value” Really Means

A professional valuation estimates value. A signed deal sets the price. Value comes from disciplined financial and operational analysis. Price reflects competition, timing, financing conditions, negotiation skill, and sometimes emotion. In private deals, price often includes post‑closing adjustments tied to performance or to representations and

warranties. What drives both value and price is the sustainability and reliability of future cash flows - the income a buyer can count on after you exit.

Is It a Business or a Job?

We assess the fundamental nature of the business early on. A true "business" possesses transferable value. A business exists when:

- Client relationships are transferable.

- There is technical knowledge or processes that are transferable.

- There is a possibility of making money in the foreseeable future.

For most small businesses, relationships and technical knowledge that produce income have business value. The tangible assets are often easy to obtain and usually do not contribute much to the overall value.

Part II: How the Valuation Process Works

Valuation is iterative. We refine conclusions as new information emerges. The process begins with a an interview to capture operations and possible financial adjustments. Next comes document collection and verification. During preliminary assessment, we check that results are reasonable, confirm operational independence, identify customer or supplier dependencies, and clarify what exactly is being sold. Coordination with your accountant improves data integrity and speed.

Part III: The Information We Need and Why It Matters

Accuracy depends on the quality and completeness of information. The following table summarizes what we request and how it is used:

Each item supports a specific part of the analysis: determining sustainable earnings, sizing working capital, identifying concentration risks, validating obligations, and revealing legal or operational constraints that could affect price.

Part IV: Adjusting Financials to Show True Earning Power

Normalization involves adjusting historical financial data to reflect sustainable, accurate earnings, leading to the calculation of Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) or adjusted EBITDA. For smaller, owner‑operated companies (typically under about $3 million in

revenue), we express earnings as Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE). For larger firms with managerial depth and continuity, we use Adjusted EBITDA. Both aim to reflect the earnings a buyer can rely on after replacing the owner at market rates and removing non‑operating noise. The difference is that SDE includes owner's salary.

Typical addbacks include owner salary and perks, family payroll and benefits, excess or non‑market rent on owner‑occupied real estate (with rent reset to market in the model), one‑time legal or consulting costs, and non‑operating items such as interest or gains and losses on asset sales. Typical subtract‑backs include replacing family wages with market‑rate equivalents, removing one‑time or non‑recurring revenue (for example, subsidies or grants), deducting required maintenance capital expenditures, and reflecting known future cost increases.

Trend analysis matters as much as totals. If SDE or adjusted EBITDA is rising, the most recent year carries more weight. If results are volatile, we average multiple years to see the underlying level. If earnings are declining, buyers will discount, assuming higher risk. We repeat normalization across at least three years to test consistency and to separate structural improvement from temporary spikes.

Part V: What Drives or Reduces Business Value

Financials show what the company earns. Qualitative factors show how durable those earnings are. We evaluate systems, people, and culture because companies with continuous‑improvement habits are more resilient; good systems let average people deliver consistent results. We review service delivery, purchasing, sales and marketing discipline (including pipeline management), turnover, age of management, post-sale retention, and financial controls. The question is simple: can the business sustain its

performance without the current owner’s daily involvement?

We then rank strengths and risks in the areas that most affect the valuation multiple: profitability level and quality, growth and stability, customer and supplier concentration, transition readiness of the owner’s role, process and systems quality, depth of key personnel, overall workforce resilience, the strength of goodwill and market relationships, and the relevance of equipment and location. Higher scores support higher multiples.

Risk reduces value. Overdependence on a handful of customers or a single technical expert, exposure to volatile commodity prices or cyclicality, weak market positioning, and lack of recurring or contracted revenue all compress the multiple. External issues also matter: pending lawsuits or disputes, lease or licensing problems, a weakening balance sheet, or deteriorating recent results can block buyer financing or lead to price reductions.

Part VI: Determining the Final Value and Sanity Testing

Once sustainable earnings are established,we apply a market‑supported multiple. The multiple is selected based on a combination of financial trends and qualitative risk factors. When choosing comparable, we consider:

- The trend of cash flows and profitability.

- The management structure and size of the company.

- Concentrations or unusual risksor the reduction of risks.

- The timing of the economiccycle and industry trends.

The Sanity Check

We ensure the calculated value is higher than the sum of tangible assets (liquidation value), as otherwise, the business might be better off parted out.

Buyer Perspective: The final valuation must be logical and realistic for a hypothetical buyer. We confirm that the resulting SDE is sufficient for the buyer to:

- Make a living (pay themselves).

- Service the debt at currentlending rates.

- Maintain at least a 25%cushion.

The outcome of the valuation is a clearly stated estimate of value and a most likely sale price range that reflects your company’s risk, growth, and financing constraints.

A clear, disciplined process, clean financials, transferable systems, stable customers, and documented risk controls will widen the buyer pool and support better terms. When it is time to sell, preparation converts your years of effort into thebest achievable price.